Page 26 - Curriculum Visions Dynamic Book. To close the book, close the window or tab.

P. 26

Landscapes of faults and rifts

Faults are surfaces (planes) of weakness in the earth’s crust that are used time after time by earthquakes. They occur because the earth’s plates are always moving. This puts great stress on the brittle crust, and so it often breaks up. Each break is a fault. Faults are a common feature of the landscape.

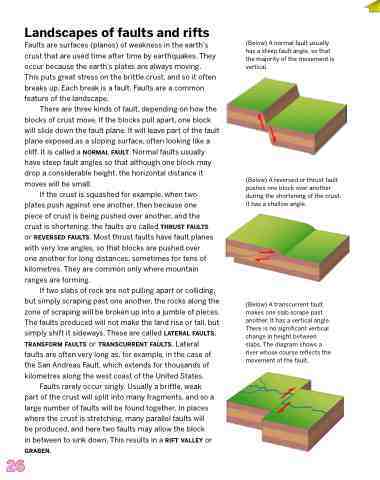

There are three kinds of fault, depending on how the blocks of crust move. If the blocks pull apart, one block will slide down the fault plane. It will leave part of the fault plane exposed as a sloping surface, often looking like a cliff. It is called a normal fault. Normal faults usually have steep fault angles so that although one block may drop a considerable height, the horizontal distance it moves will be small.

If the crust is squashed for example, when two plates push against one another, then because one piece of crust is being pushed over another, and the crust is shortening, the faults are called thrust faults or reversed faults. Most thrust faults have fault planes with very low angles, so that blocks are pushed over one another for long distances, sometimes for tens of kilometres. They are common only where mountain ranges are forming.

If two slabs of rock are not pulling apart or colliding, but simply scraping past one another, the rocks along the zone of scraping will be broken up into a jumble of pieces. The faults produced will not make the land rise or fall, but simply shift it sideways. These are called lateral faults, transform faults or transcurrent faults. Lateral faults are often very long as, for example, in the case of the San Andreas Fault, which extends for thousands of kilometres along the west coast of the United States.

Faults rarely occur singly. Usually a brittle, weak part of the crust will split into many fragments, and so a large number of faults will be found together. In places where the crust is stretching, many parallel faults will be produced, and here two faults may allow the block

in between to sink down. This results in a rift valley or graben.

(Below) A normal fault usually has a steep fault angle, so that the majority of the movement is vertical.

(Below) A reversed or thrust fault pushes one block over another during the shortening of the crust. It has a shallow angle.

26

(Below) A transcurrent fault makes one slab scrape past another. It has a vertical angle. There is no significant vertical change in height between slabs. The diagram shows a river whose course reflects the movement of the fault.